Stories Behind The Giant Falstaff Beer Cans

By Jerry Banik

April 2021

The Indiana/Illinois state line boundary marker

Three of our local landmarks stood within yards of each other on the Lake Michigan shore for decades. One was the historical Indiana/Illinois state line boundary marker, which, due to its small size and its location, very few people ever laid eyes on. Just northeast of the marker stood the mighty State Line Generating Station on its peninsula in the lake.

And just to the marker’s southwest were giant, concrete silos painted to look like cans of Falstaff beer. Countless people, especially children in their parents’ cars on their way to Chicago, watched for the huge beer cans and the Chicago Skyway, signs they were getting close to their destination.

The story of the silos and the beer they advertised goes back more than 180 years.

“The choicest product of the brewer’s art”.

The beer can silos were part of Falstaff’s Plant #11.

The plant was, and still is, often referred to as something it was not. It was not a brewery. It was a malting plant that started out on that site by Albert Schwill & Co. in 1894. It was only much later acquired by the Falstaff Brewing Corporation.

First, the Albert Schwill & Company plant. Albert Schwill was an immigrant from Germany. After serving in Indiana’s 32nd Infantry Regiment during the U.S. Civil War, Schwill got into the seed business. He specialized in grains for brewing beer, and in time began his own malting business. In 1894, “to assure a constant and premium quality source of brewing’s prime ingredient, malted barley”, he built his Improved Pneumatic Malt House on the state line. It was described as the best equipped and most conveniently arranged malt house in the country, with all the latest improvements in machinery. In 1904 it expanded and became the largest malting plant in the world.

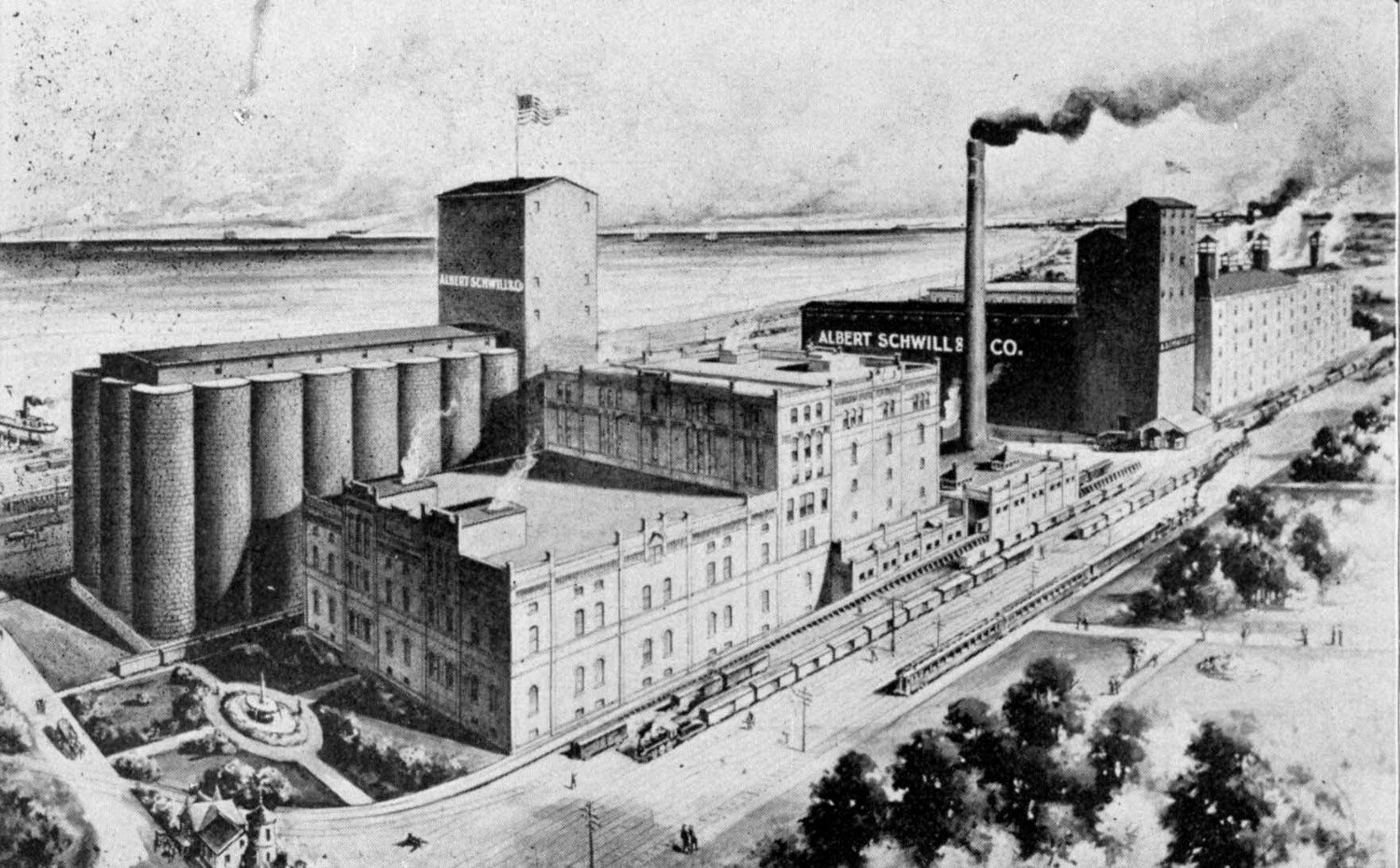

In the images below, which can be enlarged by clicking on them, are, first, the Schwill malting plant and grain elevator as it looked in 1895. The silos, which decades later would be painted as beer cans, appear in the second image, a rendering of the plant after its 1904 expansion. A clipping from the Hammond Times announces Schwill’s as the world’s largest malt house in 1907. In the final image, circa 1937, the Schwill plant can be seen with its new neighbor to the north, the State Line Generating Station. The state line boundary marker between the two plants is blocked in this view.

Falstaff beer is named for Sir John Falstaff, a hard drinking, comic character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare. He spent most of his time drinking at the the Boar’s Head Inn with other drunks and petty criminals.

As for the Falstaff beer brand, it was created in St. Louis by the Western Brewery, a company founded in 1840 by another German immigrant, Adam Lemp. That brewery closed down in 1921, and sold its Falstaff brand to the Griesedieck Beverage Company. Griesedieck brewed it in Fort Wayne, and renamed itself the Falstaff Brewing Corporation.

For the next four decades the Falstaff brand grew, and the company acquired a number of other brewers. By 1960 Falstaff Brewing was the third largest brewer in America, behind only Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz.

It was in 1961 that Falstaff purchased our local Albert Schwill malting facilities.

Falstaff’s fortunes, though, soon began to decline. By 1975, the Falstaff Brewing Corporation was only America’s eleventh largest brewer, and it was sold to the S&P Company, which owned Pabst, Stroh’s and other brands. Production of Falstaff beer in Fort Wayne ended in 1990, and the brand name became the licensed property of Pabst, which continued to produce it at other facilities.

S&P ended production of Falstaff beer altogether in 2005.

The histories of the Falstaff beer brand, the Schwill malting plant and Falstaff Plant #11 are filled with odd stories; some bizarre, some sad, some amusing. Among the most peculiar are the tragic deaths of family members of Adam Lemp, the founder of the company that created Falstaff beer back in 1840.

The Lemp family ran the Western Brewery in St. Louis for many years. In 1904, William Lemp, son of the founder, was running the company, and he was grooming one of his sons, Frederick, to take over. But when Frederick was only thirty-three years old, he died of heart failure, sending William into a deep state of depression. Soon William suffered a second blow when his closest friend, Frederick Pabst of the Pabst brewing empire, died. Shortly after that, on the morning of February 13, 1904, in William’s mansion, a servant heard a gunshot. He called William’s sons, who broke down the locked master bedroom door and found William dead, with his .38 caliber revolver nearby, having taken his own life with a shot to his temple.

William had a daughter named Elsa, who married a successful businessman, but was granted a divorce in 1919. The couple then reconciled and remarried, but just twelve days later, on March 20, 1920, Elsa shot herself dead while in bed in her home, though to this day there are some who suspect she was murdered. At the scene, William Sr.’s youngest son, William Jr., or “Willy”, said, “This is the Lemp family for you.”

By that time, Willy Lemp was in charge of the Western Brewery, but it went into decline when Prohibition was imposed. It was Willy who had to shut down the brewery and sell the Falstaff trademark to Griesedieck Beverage. On December 29, 1922, in the same family home where his father had killed himself, Willy took his own life with a pistol.

Lastly, nearly three decades later, a third Lemp brother, Charles, shot himself to death in the early morning hours of May 10, 1949, in a bedroom of that same Lemp family mansion. He was the only one to leave a note: "In case I am found dead, blame it on no one but me."

The Albert Schwill malting plant here was beset by troubles of its own long before Falstaff acquired it.

In May of 1920, alarm calls went out to Whiting and South Chicago police and fire departments. On the B&O tracks right in front of the plant, a passenger train on its way to Chicago on the wrong track ran head-on into an eastbound freight train headed out of Chicago. The papers reported that the conductor from the passenger train was dead, seven others were seriously injured and two were not expected to live. Schwill workers and onlookers from crowds of gawkers who gathered had to be dragged from adjacent tracks to avoid being run over by passenger trains that sped by.

On another occasion a truck driver making a delivery to Schwill’s turned into the plant’s entrance directly into the path of an oncoming train. He died in the burning wreckage of his vehicle.

In 1923 and again in 1929, huge fires broke out at the Schwill plant, destroying multiple buildings, injuring workers and disrupting train travel at the site.

In a more recent, horrible tragedy, in 1990, four young boys saw one of their friends fall 120 feet to his death while playing atop one of the long abandoned Falstaff grain silos.

His young friends who witnessed the accident were too afraid to tell anyone about it. They spent an awful summer hiding their secret until it was finally discovered.

The boy’s body was not found until five months after his fall.

Land, ho! Columbus discovers Robertsdale in this scene from the 1912 silent movie, The Coming Of Columbus.

Not all of the Falstaff and Albert Schwill stories are sad, though. On a lighter note, Selig Polygraph, a Chicago movie studio, produced a major motion picture in 1912, a silent movie about Christopher Columbus.

In Germany and Austria, lawsuits arose over the movie’s copyrights, and The Hammond Times ran a story about the suits.

In it they reported that the movie’s ocean scenes were filmed on Lake Michigan off Robertsdale, Gary and Indiana Harbor, and that, “In fact, in the motion picture Columbus ‘discovered’ America at Robertsdale. When the staid German judges inspect the films and see the Albert Schwill malt houses and the nearby fishing resorts looming up in the distance they will have to admire Christopher’s sagacity in doing his discovering at Robertsdale. What more can an intrepid explorer want than a cold stein and a good fish fry, such as are furnished by the Robertsdale beach bonifaces?”

Falstaff beer came to Hammond in 1939, courtesy of an East Chicago distributor.

In the 1940s, the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team, sponsored by Griesedieck Brothers beer, hired Harry Caray to announce the team’s games on radio. Holy cow!

In 1971, Caray joined the White Sox, and called games on TV over UHF channel 44, sponsored by Falstaff beer, which the Griesediecks had owned for years. Diehard Sox fans can still hear Caray calling out, “Man, what I wouldn’t give for an ice cold Falstaff right now!”

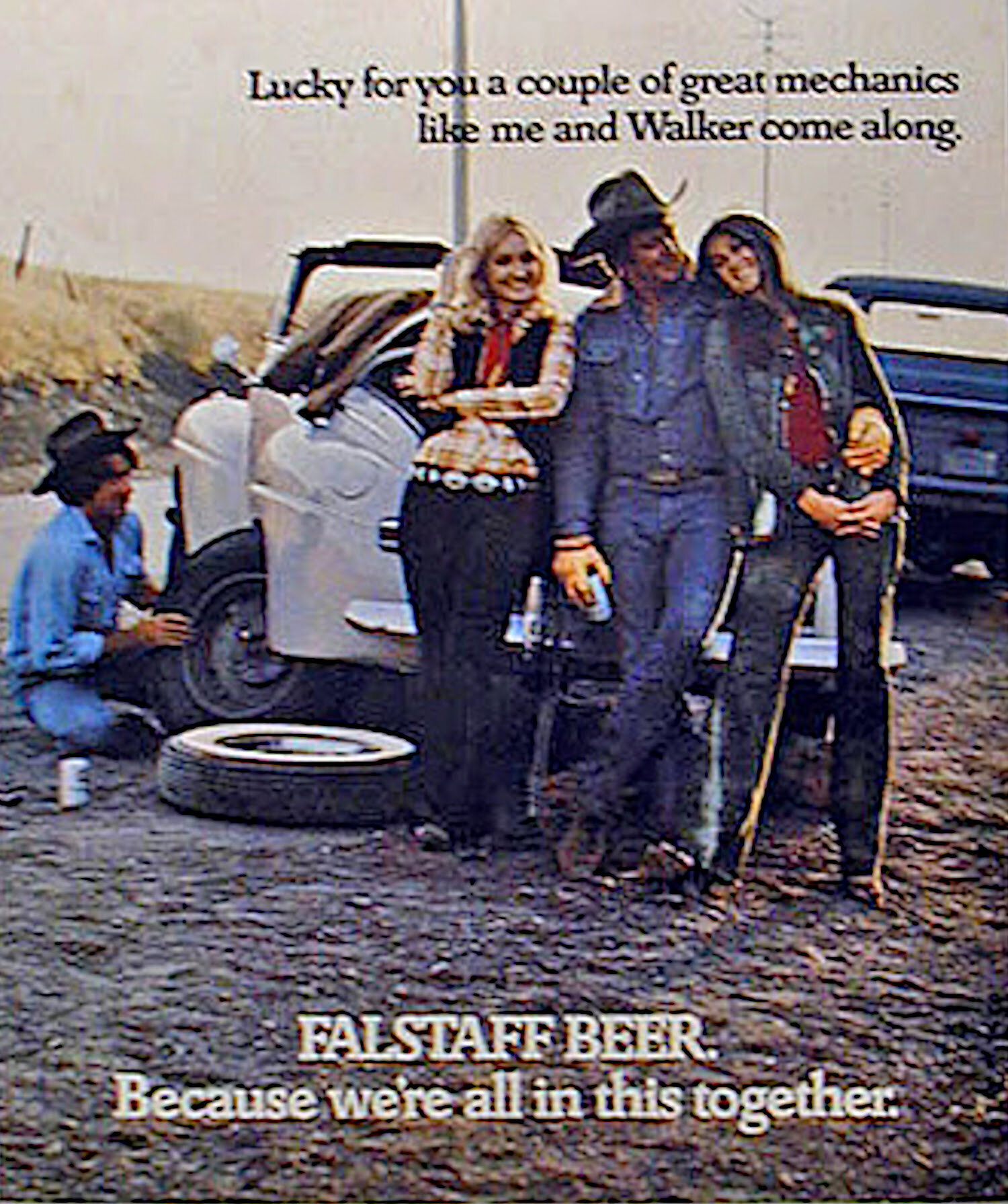

Later in the 1970s, Falstaff created a print and TV ad campaign around a couple of affable, beer drinking, modern day cowboys called Gabe and Walker, featuring a young, future movie star, Sam Elliot, as Walker. Because we’re all in this together, of course.

Falstaff’s abandoned Plant #11 and its beer can silos were eventually demolished. The job was completed in April of 1997, when the silos and the main barley processing building were dropped by explosives and disappeared into history.