Once From Whiting - Always From Whiting

Anthony Borgo July 2022

Earlier this year I received an email from a descendant of Herman Genaust. The individual was looking for the address of his ancestor who once lived in Whiting. The only details that he had was that Herman Genaust died from a dairy accident. The ball was now in my court. Over the years Whiting has had several dairies, however the main one was owned by Casper Matson.

Through some help from the Whiting-Robertsdale Historical Society we were able to locate two articles regarding Herman Genaust. The first article which was featured in the June 3, 1920 Lake County Times states Casper Matson had disposed of his interest in the Sanitary Dairy which was located on the corner of Atchison Avenue and Indianapolis Boulevard. The new proprietors were Mr. C. O’Donnell of Chicago, William Ziefenheme of Dyer, Indiana and Herman Genaust of Oak Park, Illinois.

Herman Genaust was born to parents William and Sophia in Illinois in the year 1868. He later married his wife Jessie Fay and the two had sons George Franklin and William Homer. George was born in Minnesota on June 28, 1904 and William “Bill” was born in South Dakota on October 12, 1906.

Pasteurization Machinery circa 1920s

On September 7, 1920 Herman Genaust suffered a dreadful accident at the Matson Sanitary Dairy Company, where he was serving as manager. Genaust was operating the machinery used in pasteurizing the milk and while in the act of adjusting a belt which had slipped off, his shirt sleeve got caught in the mechanism. The machine which was still in motion hoisted Herman to the ceiling. His screams of agony attracted the attention of Police Officer Niziolkiewicz, Fireman. Ollie Weigand and a man from the Whiting Garage who rushed to the scene and shut off the machine.

According to the September 7, 1920 edition of the Lake County Times. “The sight of Genaust hanging in the air was appalling and they made haste and with great difficulty had the victim disentangled and to the floor. He was immediately rushed to the office of Dr. Shimp who was assisted by Dr. Doll who found it necessary to transport Genaust to Saint Margaret’s Hospital. Herman’s arm was completely crushed and severed just below the shoulder. In addition, to his mangled arm Genaust’s ribs were badly crushed.

Herman Genaust's prognosis was good even after experiencing such a horrific accident. “In spite of Mr. Genaust’s age, being nearly seventy and the awful shock he received, it was said at the hospital that he would survive.” Unfortunately for the Genaust family this was not the case, a week later he passed away at the hospital. According to his death certificate the Genaust family was living in Whiting at the time.

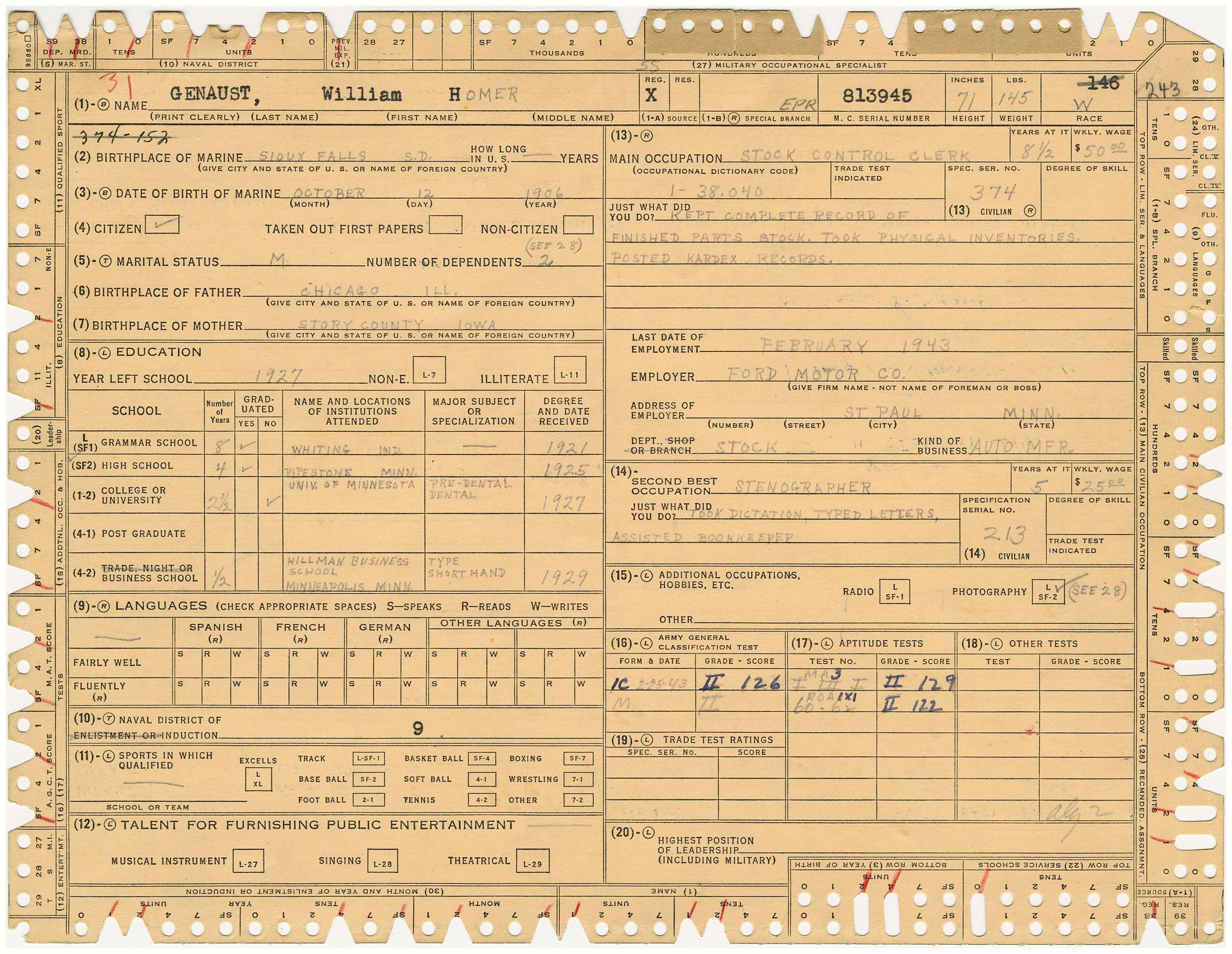

Although I was unable to find the exact address of the Genaust’s Whiting home, I was able to verify that in 1920 Franklin Genaust was a freshman at Whiting High School and according to William Genaust’s enlistment papers he attended grammar school in Whiting. However, the story was just getting started.

As I began to research the Genaust family I discovered that Bill Homer filmed the raising of the second American flag on Mount Suribachi in Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945. Genaust was a sergeant in the war correspondent division of the United States Marine Corps. Nine days after he filmed the flag raising, he was shot and killed by Japanese soldiers hiding in a cave.

Bill Genaust operated a then-modern 16 millimeter motion picture camera which used 50-foot color film cassettes. His motion picture of the flag raising became one of the best-known film clips of World War II, and documents the event famously depicted in the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia.

William Genaust

On February 23, 1945, a 40-man patrol consisting primarily of members of the Third Platoon, E Company; 2nd Battalion, and 28th Marines, 5th Division were ordered to climb up Mount Suribachi and seize and occupy the summit. After taking command of the summit Lieutenant Harold Schrier along with two other soldiers raised the battalion’s small American flag to signal the mount had been captured. The flag was attached to a Japanese iron water pipe and was erected approximately at 10:30 a.m.

Around noon, Marine photographers Bill Genaust and Bob Campbell, along with Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal, were ordered to go to the peak of Mount Suribachi. The three photographers ascended the dormant volcano along with four Marines from Second Platoon, E Company, who received orders to raise a large replacement flag at the top of the summit. Once at the top Bill Genaust with his Bell & Howell camera, stood to the left of Rosenthall, and filmed the second flag being hoisted into place by six Marines.

Genaust’s film captured the six Marines getting in place to raise the larger flag which was secured to a second water pipe. The film also depicts the raising of the flag and makeshift pole, and the securing of the flagstaff into the rocks. However, Rosenthal became famous for taking the black-and-white photograph of the second flag raising which appeared in Sunday newspapers across the nation.

William Genaust was reported missing on March 3, 1945. A day later his status was changed to killed in action. A group of marines were clearing out caves on the northern part of Iwo Jima. After throwing grenades into the cave, the soldiers wanted to double check it and asked to borrow Genaust’s flashlight. Bill said that he would enter the cave with the Marines. After crawling in, Genaust flashed his light around. There were several Japanese soldiers still alive in the cave and they immediately opened fire. As the light bearer Genaust was met with a barrage of gunfire dropping him instantly.

William Genaust received several military decorations including a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. In 1995, a bronze plaque honoring Genaust was placed at the Mount Suribachi Memorial. In addition, Every year the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation awards the Sergeant William Genaust Award recognizing the advancment and preservation of Marine Corps history.

Although William Genaust only spent a short time in Whiting he was one of ours and we should be proud of his sacrifice.