How Whiting’s Standard Oil Company Helped End World War II

Frank Vargo June 2020

As the world marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, the men and women of Whiting should be proud of the role they played in the war effort. The hundreds of workers employed by the Standard Oil Company answered the call of their nation, leaving their jobs to join the armed forces and heading to various places around the world. Standard promised that their job, or a comparable one, would be waiting for them when they returned. Their time in the armed forces would also be counted toward their seniority at the plant. Of course, not every worker left. Men and women were still needed to produce the gasoline, airplane fuel, specialty oils and greases necessary to keep our war machinery running smoothly.

This is the story of one group of workers who were instructed what to do, yet they were never informed exactly about what the result of their effort would lead to.

First, some background information.

On August 2, 1939, Albert Einstein, who had earlier fled Nazi Germany, wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt informing him of the potential of a yet not developed new weapon, an atomic bomb. While still in Germany, Einstein had heard ideas for the development of such a weapon. FDR ordered a secret group of scientists to begin working together, exploring every aspect of such a weapon and atomic energy.

Experiments began at the University of Chicago, the University of California Berkeley and Columbia University in New York. Because of the work done at Columbia, the code name Manhattan Project was decided upon. The Manhattan Project cost the United States over $2 billion in just four years. A massive uranium laboratory and enrichment site was built in a near wilderness area at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. It was called “The Secret City.”

Enrico Firmi

On December 2, 1942, Enrico Fermi created the first successful chain reaction in which atoms were split in a controlled environment. Also that year, the scientists said they needed another isolated lab. Los Alamos, New Mexico, was chosen and given the code name “Project Y.”

After three years of work, the big test came on July 16, 1945, when a bomb called “Trinity” was dropped from a tower in the New Mexico desert. Not only did the tower disintegrate, but thousands of yards of surrounding desert sand were turned into a “brilliant jade green radioactive glass.”

By now, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy had already surrendered. However, the Empire of Japan refused to end the war in the Pacific. Their emperor, Hirohito, said that the Japanese people would never surrender. They would fight from street to street all over their countryside if necessary. It looked like perhaps a million Allied soldiers and Japanese citizens might lose their lives if that were to take place.

Harry Truman

President Harry Truman had succeeded FDR when Roosevelt passed away on April 12, 1945. Truman knew nothing about the atom bomb. That’s how closely guarded this secret was.

Where does the Standard Oil Refinery in Whiting fit into the story? In December of 1943, General Leslie R. Groves met with officials from the refinery. General Groves was the officer who was heading the Manhattan Project. General Groves said, “I have a little job for your company to do for our country. It involves the separation of boron-10 into a form that can be useful for us.”

General Leslie R. Groves

Of course SOCO had many years of experience with the distillation of oil, so General Groves was confident that Standard Oil would be successful with the distillation of boron-10. At Whiting, this project was known only as “Number 4 Process Laboratory.” Refinery officials, as well as the hand- picked workers, were never told why they were working on this project. SOCO officials told everyone, “Don’t ask, because we don’t know either.”

The process design began immediately. The Number 3 boiler house was chosen because of its size and out of the way location within the refinery. A new barbed wire fence surrounded the building and refinery guards checked the identification of those workers to make sure they had the special clearance to enter.

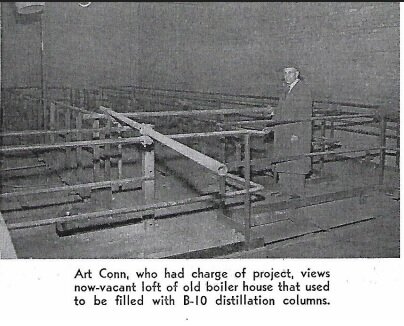

Nine distillation towers were built inside boiler house #3, each containing 30 feet of packing. The government wanted boron-10 in a concentration of a least 95%. In early 1944, the boron-10 was only enriched up to 60%, so more columns had to be added. In three months, the 95% rate was achieved. Daily production was two gallons of liquid. Of that amount, about 9% was ultimately converted into the boron-10 solid. Success was achieved. The boron-10 was valued at three times the price of gold. The refinery continued operation at the Number 3 boiler house until February 1946. Three years later, the contents of the building were dismantled. No one in Whiting was yet told why they worked on the distillation of boron-10. In August of 1945, many workers put two and two together and believed they had done their part to end World War II.

On August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb known as “Little Boy,” because of its relatively small size, was released from a B-29 bomber called the Enola Gay over the Japanese city of Hiroshima at 8:15 am. By 8:16, approximately 66,000 people had perished and another 69,000 were injured or quickly developed radiation sickness.

Nagasaki circa August 9, 1945

The Imperial Government of Japan still refused to surrender. On August 9 a second atomic bomb called “Fat Man” (because of its round size) killed about 39,000 Japanese and injured another 25,000 in the city of Nagasaki. Emperor Hirohito told his war council that Japan must surrender because of this new weapon. The final surrender documents were signed aboard the U.S.S. Missouri on September 2, 1945.

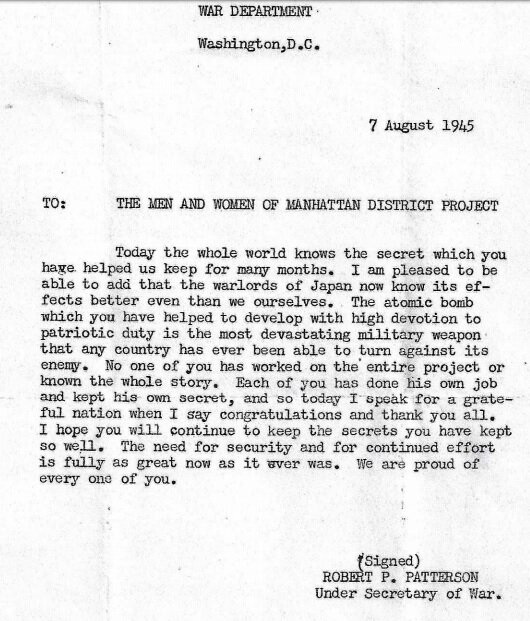

On August 7, 1945, the following message was sent to Mr. A. L. Conn who was in charge of Standard Oil’s part of the Manhattan Project.

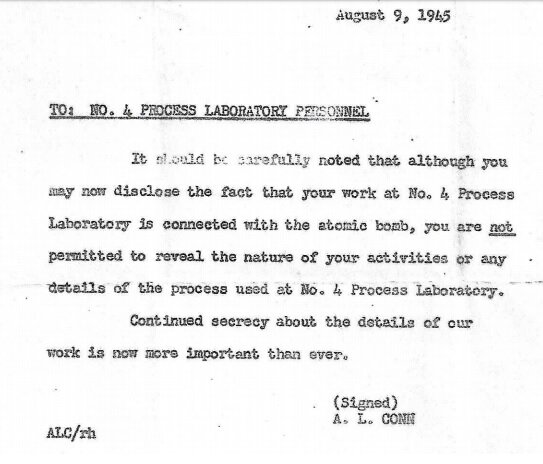

On August 9, 1945, Mr. Conn sent the first message along with this note to his workers. As you can see, the workers were told to not reveal the contents of any of these messages to anyone.

It was later revealed that the milky liquid distilled at Standard, the boron-10, was a superlative insulator from radioactive materials. It kept the bombs from exploding while still in the bomb bays of the B-29s.

It was only in 1957 that the U. S. military declassified this information. In the May 1957 issue of the Standard Torch, an article entitled “Now It Can Be Told” was published. I used this Torch article as the basis of my story.